Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: Chemistry as a Lab Science

Part a: Beyond the Scientific Method

Part 1a: Beyond the Scientific Method

Part 1b: Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

Part 1c: Experimental Design

What is Chemistry?

Chemistry is the study of the matter. Chemistry is concerned with how stuff is structured, the properties that stuff exhibits, and how stuff changes over time. By stuff, we mean the everyday materials that surround us. The world is made of stuff or matter and Chemistry seeks to understand it.

Some chemical stuff interacts and undergoes change when exposed to other stuff. We refer to this as a chemical reaction. Natural gas burns on the stove top. Food is digested in the body. Iron turns to rust over time. Plants combine carbon dioxide and water and produce more plant stuff when exposed to sunlight. Chemistry is concerned with the why and the how of chemical reactions. Chemistry seeks to predict what will be produced when stuff reacts. Chemistry also investigates what all this stuff is made of and what holds the stuff together at the particle level.

Some chemical stuff interacts and undergoes change when exposed to other stuff. We refer to this as a chemical reaction. Natural gas burns on the stove top. Food is digested in the body. Iron turns to rust over time. Plants combine carbon dioxide and water and produce more plant stuff when exposed to sunlight. Chemistry is concerned with the why and the how of chemical reactions. Chemistry seeks to predict what will be produced when stuff reacts. Chemistry also investigates what all this stuff is made of and what holds the stuff together at the particle level.

Chemistry tries to discover and describe patterns in the way that chemicals behave. Many questions in Chemistry begin with How much? and What amount? By reliance upon mathematics, chemistry represents the observed patterns of behavior in the form of mathematical models. The laws of Chemistry are represented by quantitative statements and mathematical equations. Chemistry develops models for explaining the world and for predicting what would happen under certain conditions.

Chemistry as a Lab Science

As defined above, chemistry is described as a noun – a study. It is portrayed as a body of knowledge. But Chemistry is much more than that. Much more! Chemistry is also a verb. It is something that one does. Doing chemistry involves participating in the habits, thinking, and activities that promote an understanding of the world of chemistry. As a verb, chemistry involves doing experiments and reasoning towards conclusions that can be added to the body of knowledge. As a noun – a body of knowledge – Chemistry grows in size over the course of time. And it grows in size because Chemistry is a verb.

We sometimes refer to Chemistry as a lab science. In Chemistry class, you will be doing (or should be doing) lab work. You will observe first-hand what we mean when we say some chemical stuff interacts and undergoes change when exposed to other stuff. You will observe bubbling gases and color changes. You will observe solids being formed in ways you would never expect it. You will observe smells that weren’t around when you started the lab. You will see flames and fires. You will hear pops and fizzes and maybe even a loud bang. Chemistry happens in the lab.

But in saying that Chemistry is a lab science, we mean more than Chemistry students will be doing lab work. We mean that Chemistry knowledge is discovered, acquired, and confirmed through lab work. Chemists do have opinions, make hypotheses, and entertain their intuitions about how chemicals will behave. But they know that no opinion, no hypothesis, and no intuition is worth a proverbial squat until evidence of its truthfulness is acquired through observation and data collection in the laboratory. Once laboratory evidence in support of a particular idea is acquired and confirmed by others, that idea can be incorporated into the body of knowledge known as Chemistry. This is how Chemistry as both noun and verb grows.

The Scientific Method

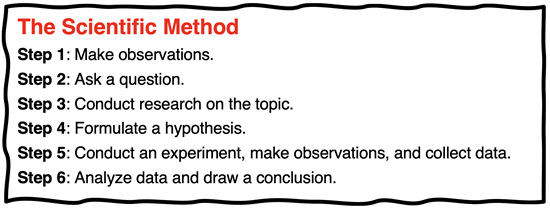

School-aged children are exposed to an idea from an early age that has come to be known as the scientific method. As it is often presented, the scientific method is a series of steps that a scientist performs in order to acquire knowledge of the world. Not all descriptions of the scientific method are identical. Some are certainly better than others. But all descriptions leave the young learner with the impression that there are distinct steps that scientists follow in their study of science. Here is an example of how the scientific method might be described:

The Truth be Told

We suspect that if 10 professional scientists were asked to identify the steps of the scientific method, we would get 10 different answers. Some might even have difficulty describing what the scientific method is. Many would state that it is not a procedure that they follow on a daily basis. Others might claim that they have never practiced the scientific method. The fact is that very few professional scientists arrive at work in the morning, roll up their sleeves, and say “Let’s get down to the business of doing the scientific method.” And scientists generally do not arrive back at their labs after lunch in the lounge and ask “OK. What step was I on again?” If all this is true, then you have to ask what’s the big deal about the scientific method?

For those not familiar with the practice of science, the scientific method can be a good description of the activities that scientists do. Scientists generally do each of the individual steps of the method. They just don’t do it in steps. They do make observations. They do ask questions. They do background research on the topics they are studying. They do form hypotheses. They do conduct experiments that involve the collection of data. And they do analyze their results and formulate conclusions. (And they do many other things as well.) It’s just that all this doing of science by the professional scientist really does not fit nicely into a method or a procedure.

For those not familiar with the practice of science, the scientific method can be a good description of the activities that scientists do. Scientists generally do each of the individual steps of the method. They just don’t do it in steps. They do make observations. They do ask questions. They do background research on the topics they are studying. They do form hypotheses. They do conduct experiments that involve the collection of data. And they do analyze their results and formulate conclusions. (And they do many other things as well.) It’s just that all this doing of science by the professional scientist really does not fit nicely into a method or a procedure.

Let’s consider scientists in the field of Chemistry – also known as chemists. There are different types of chemists. Some work in a lab at a factory and perform tests and measurements to ensure that the processes of the factory continue to run smoothly. Some chemists work in a lab at a factory to perform analyses on a product to ensure that its quality and safety is as intended. Other chemists work in a research lab to investigate ways that new products can be made or to discover new processes by which old products can be made. And still other chemists work in a lab to analyze substances to determine what they are made of. This is just four of numerous descriptions of what chemists do. While these chemists are doing all the tasks described by the scientific method, they just aren’t generally following a step-by-step method. But they are working in labs to collect data and make observation in an effort to answer questions and to confirm ideas.

Science Begins with a Question

In most instances, chemists begin with a question. The question could be a BIG ground-breaking question that has enormous global implications. These include questions like:

- Is there a cure for cancer?

- Is there a pharmaceutical that will stabilize bi-polar individuals with little side effects?

- Is there a feasible, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly alternatives to fossil fuels?

The question could also be a smaller question that is specific to a chemical manufacturer’s interest. These include questions like:

- What is the best temperature to maintain the reaction tanks used to electroplate chrome on a spoon?

- Since we increased the acidity of the reaction chambers over the past hour, how has the quality of the product changed?

- Is there a better chemical that could be used in our manufacturing process that leads to less industrial waste?

It is the question that guides and motivates the daily activities of the chemist’s experiment.

It is the question that guides and motivates the daily activities of the chemist’s experiment.

In the same way, a Chemistry student will begin their lab investigations with a question. And that question will motivate the procedural steps that are performed in the laboratory investigation. In most instances, it will be your teacher who comes up with the question and has designed the experiment for you to do. But there may be a few instances in which you must design the experiment or even develop a question that you can answer by means of a designed experiment.